IF APPLES were not remarkable enough for their variety for fresh eating or their versatility when cooked, they are utterly transformed when pressed into juice.

The most familiar result is apple juice — the clear, amber liquid with a lengthy shelf-life, available in grocery stores. Bottled apple juice is fresh cider that has been heated above 175°F for 15 minutes to 30 minutes, then filtered to a clear liquid.

Commercial apple juice is also made from concentrate and water. With the help of stabilizers and preservatives, bottled apple juice stores indefinitely.

But for apple aficionados, nothing compares to fresh apple cider, the unfiltered, cloudy, brown or copper-colored drink made solely from fresh fruit that must be refrigerated and consumed within weeks or a few months, lest it ferment.

At that point it becomes something else: the slightly fizzy, lightly alcoholic beverage known as hard cider.

Left to ferment even longer, the cider is transformed again, into vinegar, the all-purpose stuff that finds myriad uses in the kitchen and doubles as a cleaner.

But there’s more. The cider can be distilled into applejack or apple brandy, or frozen and thawed to make apple ice cider. It can be cooked down or boiled to make cider syrup, an apple-flavored alternative to maple syrup, or made into cider molasses.

Is there nothing the apple can’t do?

* * *

THIS WEEKEND, cider producers from around the country will gather in western Massachusetts for the 25th annual Franklin County CiderDays for a three-day celebration of this marvelous drink in all its permutations.

Saturday, November 2, at 1 p.m., at Northfield Public Library

Russell Powell, author of AMERICA’S APPLE and APPLES OF NEW ENGLAND

Presentation on the history of apple growing and cider making

Come and sample a variety of apples!

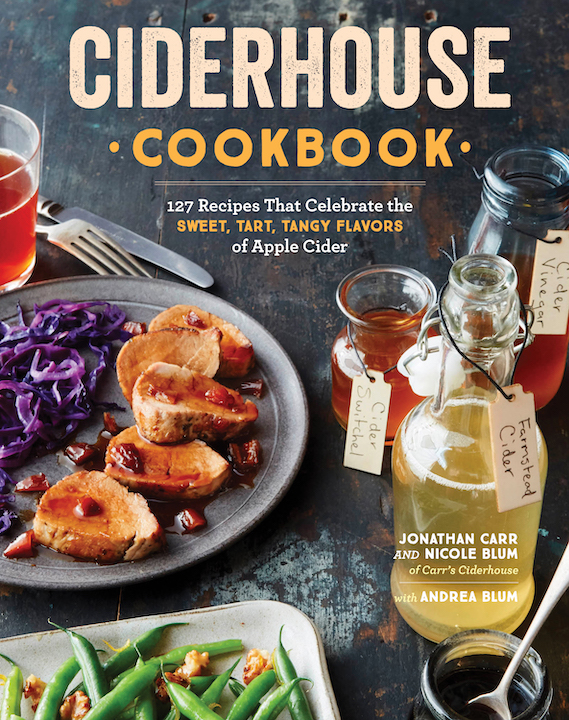

For those who can’t make it to CiderDays, a good resource is the Ciderhouse Cookbook (Storey Publishing, 2015) by Jonathan Carr and Nicole Blum of Carr’s Ciderhouse in Hadley, Massachusetts, and Nicole’s sister, chef Andrea Blum.

The authors’ enthusiasm for cider in all its forms is palpable, and the lavishly illustrated book has everything you need to know about making cider, fresh and hard, and derivatives like vinegar and cider syrup. There are plenty of recipes, two of which are included here.

Sweet and Sour Red Cabbage

“All the humble ingredients come together in a way that is pretty spectacular.”

2 T extra-virgin olive oil

1 red onion, thinly sliced

1 small red cabbage, cored and very thinly sliced (about 1/4 inch)

1/4 c hard cider

1/2 t sea salt

1/4 c cider syrup

Heat the olive oil in an enameled pan with a lid over medium heat. Add the onion and sauté until translucent, about 10 minutes. Stir occasionally so the onion doesn’t burn.

Add the cabbage and stir to coat with the oil and onion. Cook for a few minutes.

Pour in the hard cider, sprinkle with the salt, stir, and cover with the lid. Reduce the heat to low and cook, stirring occasionally, until the cabbage is tender but not mushy, 10 to 15 minutes.

Remove the lid and pour in the syrup, stirring to distribute. Cook for 1 minute, then remove from heat. Season to taste.

Cider Syrup – Glazed Scallops

Serves 2

“We were first introduced to cider-glazed scallops at a gorgeous restaurant up the road called the Blue Heron, in Sunderland, Massachusetts.”

2 T extra-virgin olive oil, plus more as needed

16 large scallops (approximately 1 pound)

1 small shallot, minced

1/4 c dry hard cider

2 T cider syrup

1/4 t salt

2 T chopped scallion, for garnish

Coat a large skillet with the oil and heat over medium heat. Place the scallops in the hot pan and brown on one side, about 2 minutes. Flip and brown on the other side, about 2 minutes. Remove the scallops from the pan to a plate.

Add a bit more olive oil to the pan if it is dry. Add the shallots and cook over medium heat until they become translucent, about 1 minute.

Add the cider to the saucepan and cook it for about 1 minute. Add the syrup and salt, whisking to combine, then put the scallops back in the pan, flipping them to coat both sides evenly. Cook until the glaze begins to darken, about 1 minute. The glaze will caramelize quickly, so don’t walk away from the pan. Plate the scallops and pour any extra glaze from the pan over the top. Garnish with the scallions.

Excerpted from Ciderhouse Cookbook (c) by Andrea Blum, Nicole Blum, and Jonathan Carr. Used with permission from Storey Publishing.

* * *

ANY APPLE can be used in fresh or hard cider, even an unnamed chance seedling, and each variety contributes a distinct mix of sweet, acid, and astringent properties. All-purpose heirlooms like Ashmead’s Kernel and Golden Russet are particularly prized for cider, while varieties like Tremlett’s Bitter, Harry Masters Jersey, Yarlington Mill, Dabinett, and Redfield, are cultivated exclusively for fresh and hard cider.

Large-scale makers of fresh cider must rely on varieties planted in sufficient quantities to meet their high demand, which rules out most heirlooms. Carlson Orchards in Harvard, Massachusetts, for example, uses plenty of McIntosh, Gala, Idared, Red Delicious, and Cortland in its fresh cider, and other New England staples as they are available.

Since 1996, following an isolated case of e-coli contamination in the Pacific Northwest, most of America’s fresh cider has been pasteurized. The federal government began requiring warning labels on all unpasteurized fruit and vegetable juice containers after the incident at the Odwalla, Washington, juice company, and most fresh cider now is either exposed to ultraviolet rays to kill potential pathogens, or flash pasteurized, its temperature raised to 160°F for 14 seconds and then quickly cooled.

All sales of unpasteurized cider must be direct to the consumer, on the farm where it is made or off the farm at farmers markets and special events, and it must have a proper warning label on each container.

Come to CiderDays this weekend and see if you can tell the difference between pasteurized and unpasteurized fresh cider!